The Oregon Trail Moment for Artificial Intelligence Is Quickly Ending

Raise your hand if you’ve ever held a big ol’ floppy disk before!

If I could look through this screen I’d see a lot of hands held high :)

Way before we all had three devices on us (yea, I see you with the watch, phone, and laptop over there).

And way before we used computers for work, communication, research, writing, music, art and thousands of other creative pursuits.

There was Oregon Trail.

In my school we had a converted custodial closet that was turned into a “Computer Lab” with two and then eventually three computers.

We’d take turns — normally on Friday’s — inserting that floppy disk and entering the world of Oregon Trail.

Maybe you tried to hunt rabbits, but if you were anything like me, buffaloes were what you hoped for a chance to hunt.

The trials and tribulations of Oregon Trail usually ended in a fight with dysentery. Sure we learned some geography and history along the way, but I came home excited due to the magic of computers and what they could do, and how much fun I had playing that game.

Artificial Intelligence’s Oregon Trail Moment

BBC ran a really interesting article on both the fanfair, and criticism, Oregon Trail has received in the 50 years since it was released:

The Oregon Trail was first developed by a team of three teachers from Minnesota, US in 1971. The earliest iteration ran on a computer that didn't even have a screen. Students would read their progress on sheets of paper the computer printed out after every move.

The game was eventually picked up by the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium, and received its first wide release in 1974, when it was made available to educators across the state. The Oregon Trail was an immediate hit, but it wasn't until Bouchard's sequel for the Apple II that it became a sensation.

"The lasting fame of the game is a fascinating puzzle," says R Philip Bouchard, team leader and designer of the classic 1985 version of The Oregon Trail, released on the Apple II computer. But on a basic level, it's simple, he adds. "Most kids played The Oregon Trail at school," Bouchard says. "How often do you get to do really fun things at school?"

The last quote is the one that got me. Oregon Trail was fun. It may have led to learning as well, but I remember the game and not the content (maybe my experience is different than yours but I’ve had this conversation with many people).

There have been plenty of Edtech moments like Oregon Trail and “Where in the World Is Carmen San Diego?”.

Often the novelty drives attention, whether it is a game-like experience, or a new type of learning not seen in many classrooms.

Artificial Intelligence has arrived and it has much of the same feeling right now as that Oregon Trail moment.

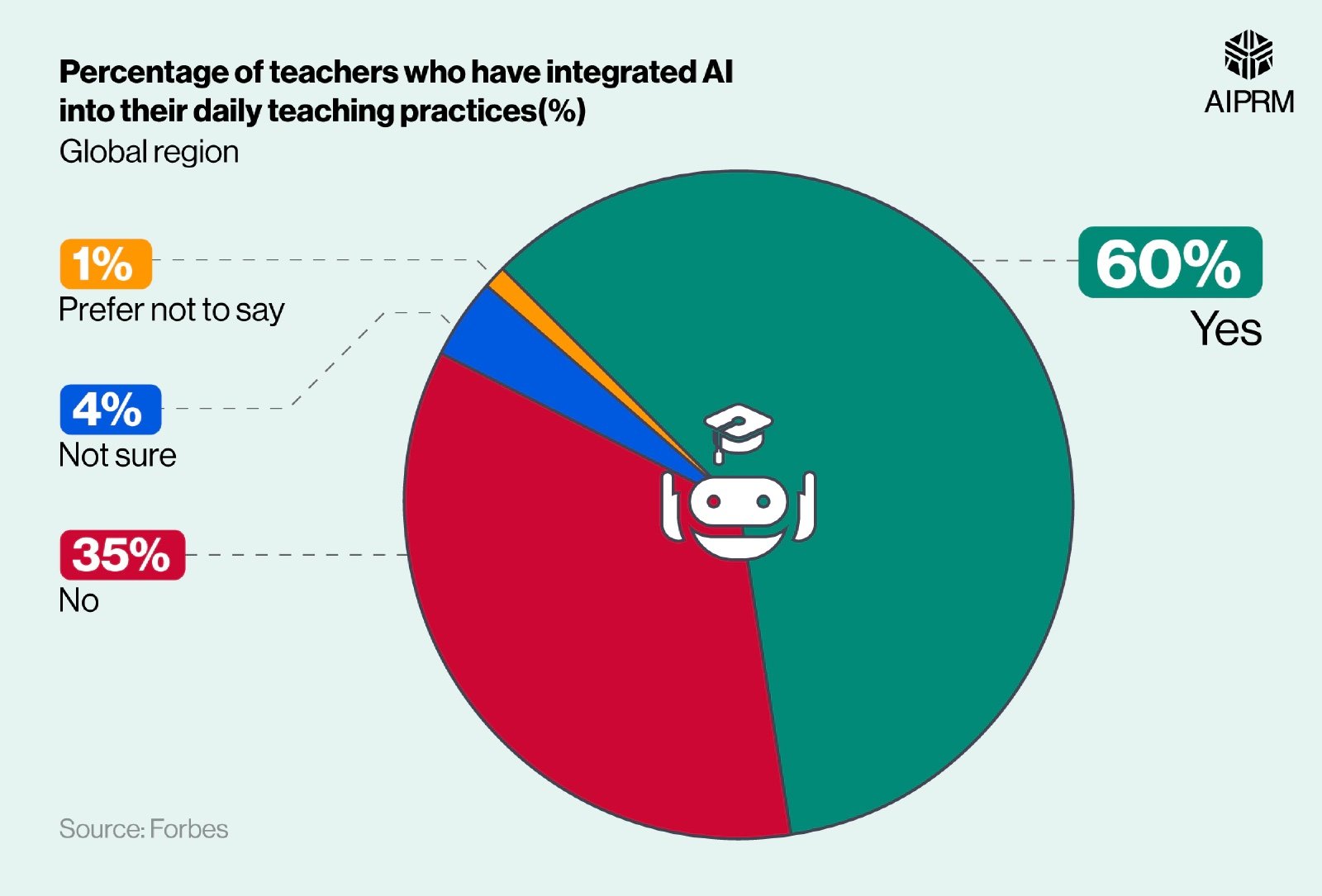

According to a Forbes survey, approximately three in five (60%) teachers interviewed by Forbes claim to have integrated AI into their daily teaching practices, with around one in three (35%) saying they haven’t.

What are the teachers using the AI for? Well, games of course.

Sure, there are other uses (as I’ve written about extensively). But, the survey shared here by AIPRM and Forbes is clear that “AI-powered educational games” are at the top of the use-case list.

The Shift From “Toy” to “Useful”

I firmly believe we are at the “Oregon Trail” moment with AI in education.

This time the shift from “toy” to useful” to “different” will be much quicker and much more impactful (also, a way different impact than what Altman and Khan predict).

Whether we like to admit it or not, this process happens with new technologies over and over again as described in EveryPixel Journal:

Printing Press? Oh, that looks like it could be fun. Then professional copyists, the Church, and general public all had concerns. It took 50 years for it to be widely accepted.

Telephone? A few months before Alexander Graham Bell unveiled his device, The New York Times published a note accusing Philipp Reis of “deliberate malice” over his telephone-like device. The fear was that if people in America got telephones, they would no longer show up at national celebrations, exhibitions, and concert halls, but would retreat to their rooms and listen “to the trembling telephone.”

Personal Computers? When it came to computers, there was a kind of panic that was mostly about potential mass job loss coupled with the confusion of not being able to figure out how to make the machine work. Even experts and journalists, who are usually expected to be advocates of technology, were sometimes skeptical about computers. They didn’t believe that computers would become a part of everyday life and considered computers in the home to be a fad.

This impacts education in so many ways.

I remember “Classrooms for the Future”. A state grant in Pennsylvania that brought 1-to-1 devices in some of our classrooms via Macbook computer carts.

It was one of the early highlights of my teaching career to be able to harness the power of technology with my students. Writing in a Google Doc for the first time felt like magic. Collaborating with peers and students in real-time completely changed how I taught and how my students learned.

We used Web 2.0 tools like Wordle, Glogster, Blogger, and so many others.

Sometimes it was worth it to use this new technology, and many other times it was not.

But, we were learning together, trying new things, and seeking out new and better ways to create engaging learning experiences.

Flash forward a year or two, and I was in the middle of a department meeting. We were discussing upcoming changes to our curriculum when our 1-to-1 initiative came up.

The conversation went all over the place, but one of my colleagues made a comment I’ll never forget.

She said, “Does anyone else feel like sometimes we are using these laptops as teenage pacifiers?”

The room was silent. But, everyone was on the same page.

We knew what she was referring to: Instead of using the technology for new and better learning experiences, I would often use it for compliance-based learning. Because the technology was still in it’s honeymoon phase, the students would go through the motions, using the tech, and would be “well behaved” in class during these activities.

The next day as my students were using their laptops to edit their essays, I wondered: Is this meaningful? Is it relevant? Is it engaging? Or am I happy because the class is easy to manage due to these “teenage pacifiers”?

I answered that question rhetorically, thinking back on my own writing and research process. My mom would always tell me I had it so easy. Back in her day she would have to go to the library, pull out books, read the books scanning for passages and quotes that would be useful and support her argument/thesis.

She would use the Microfiche or Xerox copier to make copies, cut and paste the quotes into her document on the typewriter. This is where those “cut, copy, and paste” terms come from!

My process was very different. And each time tech improved, it also became less time consuming. Microsoft Word was better than Word Perfect. The save and sharing functionality of Google Docs made it more useful than Word for working on assignments together with editing/revision etc.

The list could go on. Now my students were in front of me editing their papers that I could see in real-time, give feedback in-person and in online comments, and it was only the start of how computing was useful in teaching and learning.

The Shift From “Useful” to “Different”

All of these previous technologies moved into the “useful” category at different speeds. We’ve seen Artificial Intelligence already jump into the useful category for many professions that are using it for a specific purposes.

The same is true for teaching, learning, and education in general. Last year I did a free webinar (you can watch below) where I showed three specific ways I’ve been using AI with a purpose to make learning more meaningful, relevant, and engaging.

Since then much has changed, but a lot of public perception has not changed. The "AI is just a fad, or can only be used for cheating” conversation continues to happen in schools around the world. Similarly, there are folks touting how it will change the world and everyone will lose their jobs.

What both sides miss is the obvious lesson we have from history. Moore's Law, formulated by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore in 1965, states that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles approximately every two years while the cost halves. This observation has been remarkably accurate for decades and has driven exponential growth in computing power and efficiency. Every school in the world should be teaching this and the impact of what happens if it continues.

This has enabled the rapid advancement of AI by providing increasingly powerful hardware at lower costs. This exponential growth in computing power has allowed for the development of more complex AI models and algorithms. A new piece in Time by Garrison Lovely goes into great detail, “Why AI Progress Is Increasingly Invisible”.

AI researcher and mechanical engineer, David Shapiro, summed up our call to action in a recent post:

Think about this for a second. When Ford rolled out the Model T, they were literally bolting bicycle and wagon parts onto these things because nobody had paved roads yet. No traffic lights. No safety belts. No traffic laws. Nothing. Zero infrastructure. It was little more than guesswork in a lab coat.

So while all the brilliant minds in the labs keep perfecting the base [AI] technology – and believe me, they're doing incredible work – somebody needs to build the roads. That's where we come in.

None of this is obvious right now. But give it time – we'll figure it out, build it, perfect it. And then everyone will look back and say "well of course that's how it had to work." Just like they did with cars. Just like they did with the internet. Just like they always do.

Welcome to the real AI revolution. The one that happens after the labs do their magic. Now it's time for the rubber to meet the road and for us integrators to roll up our sleeves and get our hands dirty.

What are we going to do in education? I for one, want to help build these roads.

I’m not interested in AI being used solely for games. I’m not interested in it replacing the human part of a very human process (learning). And I’m not interested in it being a “tech pacifier” that leads to more compliance, and less engagement.

But, we don’t need to wait. We need to tinker, explore, and use these technologies. We need to discuss the various pros, cons, and real ways folks are already using AI with a purpose.

And we need to build and create. I recently built my first web app using AI (Cursor). It is a Pomodoro Timer for Writing Workshop. I learned so much in the process of using AI to help code and make this tool. Now, I’m working on my next project, because the learning is helping me become a better teacher, just as it is always the case.

What I shared below in this free webinar/training is only the start of the movement towards useful AI. No games, just a focus on learning that is meaningful, relevant, and effective.

Educators everywhere are sharing (as we do), and I can’t wait to see what the future holds as we build these roads together.