The Struggle To Learn In An Age of Continuous Partial Attention

You’ve probably heard folks over the years say things like, “Addiction to our phones is real”, or “They make video games to increase dopamine”, and of course, “The scrolling on apps like Instagram, FB, and TikTok are just like the casino games”.

You might have even experienced that nagging feeling when you have a minute of wait time or boredom, and your hand reaches subconsciously for your device…

Believe me, it’s not just you. It’s me. It’s most of us.

In my last article, we covered the reality of teaching in an era of distraction.

The flip side of that is what’s happening with our learners.

They are struggling with this new reality as well.

Turns out, it’s not that easy to learn in a state of continuous partial attention.

What is Continuous Partial Attention?

Continuous partial attention – or CPA – was a phrase coined by the ex-Apple and Microsoft consultant Linda Stone. By adopting an always-on, anywhere, anytime, any place behavior, we exist in a constant state of alertness that scans the world but never really gives our full attention to anything.

In the short term, we adapt well to these demands, but in the long term, the stress hormones adrenaline and cortisol create a physiological hyper-alert state that is always scanning for stimuli, provoking a sense of addiction temporarily assuaged by checking in.

When I first heard of this term, it instantly resonated and made sense. What is fascinating is that Linda Stone has been writing about this phenomenon for more than a decade.

It can often be mistaken as multi-tasking, but as Stone points out, they are two vastly different attention strategies:

Continuous partial attention and multi-tasking are two different attention strategies, motivated by different impulses. When we multi-task, we are motivated by a desire to be more productive and more efficient. Each activity has the same priority – we eat lunch AND file papers. We stir the soup AND talk on the phone. With simple multi-tasking, one or more activities is somewhat automatic or routine, like eating lunch or stirring soup. That activity is then paired with another activity that is automatic, or with an activity that requires cognition, like writing an email or talking on the phone. At the core of simple multi-tasking is a desire to be more productive.

In the case of continuous partial attention, we’re motivated by a desire not to miss anything. We’re engaged in two activities that both demand cognition. We’re talking on the phone and driving. We’re writing an email and participating in a conference call. We’re carrying on a conversation at dinner and texting under the table on our iPhone.

Continuous partial attention involves a kind of vigilance that is not characteristic of multi-tasking. With cpa, we feel most alive when we’re connected, plugged in, and in the know. We constantly SCAN for opportunities – activities or people – in any given moment. With every opportunity we ask, “What can I gain here?”

I’ve reminded myself time and time again, that I don’t need to look at my phone, check my email, or respond right away to that text message or notification.

I’ve put my phone on silent mode as much as possible.

But the notion of “scanning for opportunities” and being plugged in still gets me more often than not.

Yet, there are a few tasks and activities that take away that feeling. When I’m teaching and engaged in a lesson or talk, I rarely have CPA. When I’m coaching, that nag to check my device goes away completely. When I’m creating and problem-solving something I may still be using a device, but in ways that keep me away from the need to check, especially when in a state of flow. When I’m playing with my kids, or a sport, or a game…the experience supersedes CPA.

But, whenever I am going through the motions and doing low-level cognitive work, or tasks, my mind wanders and my CPA kicks in strong.

What Happens When CPA Becomes The Norm?

Imagine you are a middle school or high school student. You have six or more class periods in a school day.

You are trying to keep up with the demands of homework, in-class activities, studying, sports or extracurricular activities, and a social life.

On top of all that, you live in a world of constant, instant, communication and information.

Your laptop is filled with reminders for school, assignments, emails, and your calendar.

Your phone is a never-ending connection to the good and bad of your social life. Drawing you closer to friends and family, but removing any barriers of space and time that you need to decompress.

Remember when we used to say “BRB”? There is no “be right back” in today’s world of continuous partial attention. Over 10 years ago, in a world that was not as connected or distracted as we are now, Stone referenced that the issue is not with CPA, but instead when that feeling of CPA happens on an ongoing continuous pattern day in and day out.

Continuous partial attention is an always-on, anywhere, anytime, any-place behavior that creates an artificial sense of crisis. We are always in high alert. We are demanding multiple cognitively complex actions from ourselves. We are reaching to keep a top priority in focus, while, at the same time, scanning the periphery to see if we are missing other opportunities.

Over the last twenty years, we have become expert at continuous partial attention and we have pushed ourselves to an extreme that I call, continuous continuous partial attention.

The “shadow side” of cpa is over-stimulation and lack of fulfillment. The latest, greatest powerful technologies are now contributing to our feeling increasingly powerless. Researchers are beginning to tell us that we may actually be doing tasks more slowly and poorly.

And that’s not all. We have more attention-related and stress-related diseases than ever before. Continuous continuous partial attention and the fight or flight response associated with it, can set off a cascade of stress hormones, starting with norepinephrin and its companion, cortisol.

When CPA is non-stop and ongoing, we head down a path of serious over-stimulation.

This impacts us as learners, but more importantly as human beings.

I think it would be easy to say, “Well, then let’s just get rid of the phones! Problem solved.”

I wish it was that easy.

Are teachers going to get rid of their phones? Are we going to remove all devices from the learning environments and act like that will help prepare kids for a world where information will always be at their fingertips? Are we going to remove ALL devices and still focus on compliance-based programs and textbooks where lectures, notes, and tests are the norm (when we know that doesn’t lead to retention or transfer)?

In some contexts, I’m sure it may help. As Andrew Sullivan pointed out in 2016, “We all understand the joys of our always-wired world—the connections, the validations, the laughs … the info. … But we are only beginning to get our minds around the costs.”

The main issue with banning technology is about our connection to these devices—even when we don’t have them. Edutopia shared a 2017 study that focused on what happens when we put the cellphones away:

Students who split their attention between a learning task and texting on their cell phones or accessing Facebook, for example, perform poorly when compared to students who are not dividing their attention.

However recent research from the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research suggests that cell phones might have a negative “upstream” impact on learning, too. The authors propose that the mere presence of a cell phone, even when it is silenced and stored out of sight, might be undermining our ability to focus.

It may seem like an “either-or” decision. It’s not.

There is so much gray area to be discussed. School safety is just one of the topics parents bring up time and time again when schools, states, and even countries ban devices.

At the top of my list, is a question that comes to mind often: What are we hoping students get out of their schooling experience? What is the goal of 13 years in K-12 classrooms?

Neither Good Nor Bad

Interestingly, Linda Stone’s most recent takes on CPA have been focused a bit on school and the need for a variety of attention strategies in life.

Continuous partial attention is neither good nor bad. We need different attention strategies in different contexts. The way you use your attention when you're writing a story may vary from the way you use your attention when you're driving a car, serving a meal to dinner guests, making love, or riding a bicycle. The important thing for us as humans is to have the capacity to tap the attention strategy that will best serve us in any given moment.

From the time we're born, we're learning and modeling a variety of attention and communication strategies. For example, one parent might put one toy after another in front of the baby until the baby stops crying. Another parent might work with the baby to demonstrate a new way to play with the same toy. These are very different strategies, and they set up a very different way of relating to the world for those children. Adults model attention and communication strategies, and children imitate. In some cases, through sports or crafts or performing arts, children are taught attention strategies. Some of the training might involve managing the breath and emotions---bringing one's body and mind to the same place at the same time.

Here lies the major issue in many of our learning environments.

CPA has become continuous in many school settings because of the way our day and schools are structured.

You can’t get in a state of flow if you are changing classes frequently, and being asked to consume and note-take for the majority of your class time.

Between an unrealistic set of standards to cover from states and national organizations, to bloated curricula and programs that encompass “covering” all those standards, and then a push for fidelity to make sure we get everyone ready for tests—no wonder it is a neverending battle for student attention and engagement.

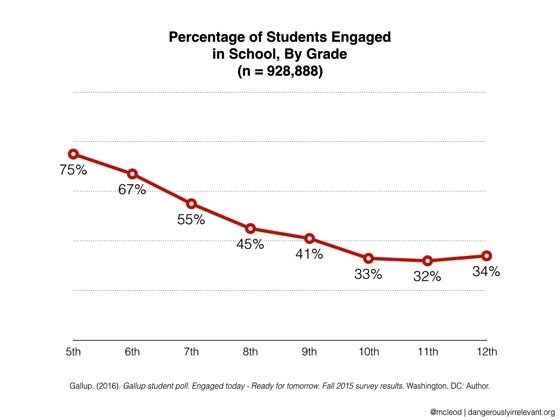

Just look at this chart from Scott McLeod showing the results from a million students surveyed on their schooling experience. Every year in the school system leads to less and less engagement.

This probably isn’t news to you. As someone who taught kids in 7th and 8th grade, and then taught a lot of those same students in 10th, 11th, and 12th grade — I saw it firsthand in my classes.

But it is an important context for our discussion on Continuous Partial Attention.

It’s like we’ve created the perfect scenario for CPA to happen over and over again.

If the learning has no relevance, of course, we are going to want to check our phones and notifications. If the experience is not meaningful, why wouldn’t we be distracted and disengaged?

In one of her most recent interviews in the Atlantic, James Fallows dug into solutions for living in a world of CPA with Linda Stone. Her answers and sharp takes on schools may resonate with you as it did with me:

Let's talk about reading or building things. When you did those things, nobody was giving you an assignment, nobody was telling you what to do--there wasn't any stress around it. You did these things for your own pleasure and joy. As you played, you developed a capacity for attention and for a type of curiosity and experimentation that can happen when you play. You were in the moment, and the moment was unfolding in a natural way.

Self-directed play allows both children and adults to develop a powerful attention strategy, a strategy that I call "relaxed presence."

You were in a state of relaxed presence as you explored your world. At one point, I interviewed a handful of Nobel laureates about their childhood play patterns. They talked about how they expressed their curiosity through experimentation. They enthusiastically described things they built, and how one play experience naturally led into another. In most cases, by the end of the interview, the scientist would say, "This is exactly what I do in my lab today! I'm still playing!"

An unintended and tragic consequence of our metrics for schools is that what we measure causes us to remove self-directed play from the school day. Children's lives are completely programmed, filled with homework, lessons, and other activities. There is less and less space for the kind of self-directed play that can be a fantastically fertile way for us to develop resilience and a broad set of attention strategies, not to mention a sense of who we are, and what questions captivate us. We have narrowed ourselves in service to the gods of productivity, a type of productivity that is about output and not about results.

We know this to be true.

We see it in our lives and with our learners.

We exist in the same lived experience, and even as adults we struggle to learn in a world of continuous partial attention.

Maybe the easy solution is getting rid of phones. France made headlines in 2018 when they banned mobile devices from classrooms of kids 15 years and younger. Recent reports say that students are still allowed to carry them to and from class, just not use them. And other reports say that despite the ban, cell phone use persists.

So, maybe that solution is not as easy, or effective, as we may hope.

There is another solution. One that requires more work.

It changes the game of school, and in doing so, puts students in situations that demand their full attention.

We can see it working at a public high school in Minnesota and a school district in Pennsylvania. It’s happening in New York City middle schools, and elementary schools in Arkansas.

In all kinds of public, charter, and private schools around the country and the world, there are examples of meaningful and relevant learning experiences that look, feel, and work differently than our traditional school model.

In our third article in this series, we’ll be asking the question, “How can we expand this growing trend so that every kid can have an experience like the students in these schools?”

The answer, backed by lots of research, might be our best solution to living, teaching, and learning in a world of CPA.

Continue Reading