Lessons From “The Anxious Generation” For Educators and Parents

In an era where anxiety and mental health concerns are at the forefront of discussions about our youth, Jonathan Haidt's book The Anxious Generation has sparked both acclaim and controversy. I’m sure, like me, most of you have heard the talking points and soundbites from this book, but I wanted to take a closer look on it’s influence and impact on education.

I get to work with schools, organizations, parent groups, and conferences — this book, and the main four recommendations have been on everyone’s mind. I’m often asked questions about my opinion, and as you can see from the lengthy article below, my thoughts are nuanced around this topic and the recommendations to:

Not give kids smartphones before high school

No social media before 16

Phone free schools (the one I’m asked about the most)

More independence, free play, and responsibility in the real world

The Anxious Generation dives into the various societal shifts contributing to the growing unease among our youth (and adults). It offers a thought-provoking analysis of social media, overprotective parenting, and media polarization.

However, Haidt's work has not gone unchallenged. Critics argue that some of his conclusions oversimplify complex issues, while others believe his emphasis on resilience and free play minimizes the legitimate struggles faced by today’s youth. Despite the debates surrounding Haidt's ideas, the lessons from his work provide a crucial lens through which to examine the forces shaping the education right now, and in the future.

Let’s dig in.

5 Lessons From The Anxious Generation For Educators And Parents

#1: Research can go both ways

Maybe the biggest lesson from the book, is that the research is so compelling. From a correlational standpoint, we can see the connection in the rise of mental health, anxiety, depression, loneliness and self-harm tied to the cultural shift of youth using phones and social media in unhealthy ways (and overall time spent on these devices and platforms).

In fact, when I first read the book, I was honestly shaken by some of the research and studies shared in the first three chapters. I’m a father of five, and my 15 year old daughter has a phone and social media, my 12 year old son and 10 year old son have an Apple Watch, and my 8 year old and 3 year old daughter use iPads to watch shows and movies.

The studies and overall thesis make a ton of sense to me, and helped lean me in the direction of limited phone use (if at all) in schools, and continuing with the no phone for as long as possible for my 12 year old (which was already the plan, as the watch seems to work well for us and him right now).

But, as someone who works in a lot of schools, and sees many different learning communities, I wondered if there was more to this story that was missing.

That’s when I stumbled across this review from the New York Times. It brought up the idea that the research was not as conclusive, and the missing nuance from the book. It wasn’t only The NY Times that had an issue.

As author Melinda Moyer points out, “plenty of critiques have appeared, including in Nature, Romper, The Guardian, The Washington Post, The Daily Beast, Reaso Platformer, and on Substack (like this one by Dr. Jacqueline Nesi, who studies teens and social media at Brown University, and this one by clinical psychologist Emily Edlynn). Some of these pieces raise concerns that I’m not going to address here, so I encourage you to read them, too.”

Particularly, this piece in Nature from Candice L. Odgers, really hit home. She is the associate dean for research and a professor of psychological science and informatics at the University of California, Irvine. She also co-leads international networks on child development for both the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research in Toronto and the Jacobs Foundation based in Zurich, Switzerland.

Hundreds of researchers, myself included, have searched for the kind of large effects suggested by Haidt. Our efforts have produced a mix of no, small and mixed associations. Most data are correlative. When associations over time are found, they suggest not that social-media use predicts or causes depression, but that young people who already have mental-health problems use such platforms more often or in different ways from their healthy peers1.

These are not just our data or my opinion. Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews converge on the same message2–5. An analysis done in 72 countries shows no consistent or measurable associations between well-being and the roll-out of social media globally6. Moreover, findings from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study, the largest long-term study of adolescent brain development in the United States, has found no evidence of drastic changes associated with digital-technology use7. Haidt, a social psychologist at New York University, is a gifted storyteller, but his tale is currently one searching for evidence.

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00902-2

I applaud Haidt for taking a stance, and writing a book that has brought these huge issues to the forefront of the public. It’s important for all of us to go beyond the graphs, stories, and research shared in the book, and I’m hoping this article will give you some jumping off points to dive into both sides of the argument.

#2: Confirms what we’ve experienced - phones and social media are impacting our youth

To give Haidt credit, he posted a whole host of Collaborative Review Docs on the research literature in February 2024. Here’s what he had to say about the research and his process for sharing these documents:

When I began to study the effects of social media on teen mental health, in 2019, I found it impossible to keep track of the many conflicting studies. I started collecting the most important ones in a Google document, then I started organizing them by method, and then I invited other academics to tell me what I had missed or gotten wrong. These publicly visible “collaborative review” documents make it easy for anyone to acquaint themselves with the research literature on the many topics listed below. They offer the abstract and a direct link to each study. I invite any academic researcher to request editing permission for any of the docs and then add studies, comments and objections. Most are curated by Zach Rausch and me, sometimes along with an expert on that topic.

One of the quotes that jumped out to me did not come from Haidt. It came from the U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy.

“Adolescents who spend more than 3 hours a day on social media face 2x the risk of anxiety and depression symptoms. And the average daily use in this age group, as of the summer of 2023, was 4.8 hours per day.”

Since 2010, we have seen a rise in the following:

Depression - 150% increase in depressive episodes since 2010 (U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health)

Loneliness (Monitoring the Future)

52% increase in children’s screen time (just from 2020-2022)

Feelings of Despair (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System)

Share of teens who say they are online ‘almost constantly’ has doubled since 2014

And the list could go on. You get the point, because as I was reading, I got the point. We’ve seen this change. We’ve witnessed it ourselves with not only youth but also adults.

Phone and social media addiction can be real. It has led to a world of CPA. Continuous partial attention – or CPA – was a phrase coined by the ex-Apple and Microsoft consultant Linda Stone. By adopting an always-on, anywhere, anytime, any place behavior, we exist in a constant state of alertness that scans the world but never really gives our full attention to anything.

In the short term, we adapt well to these demands, but in the long term, the stress hormones adrenaline and cortisol create a physiological hyper-alert state that is always scanning for stimuli, provoking a sense of addiction temporarily assuaged by checking in.

The youth are in crisis right now. Maybe it’s not solely due to phones/social media, but that was one of the biggest changes between 2010 and 2015.

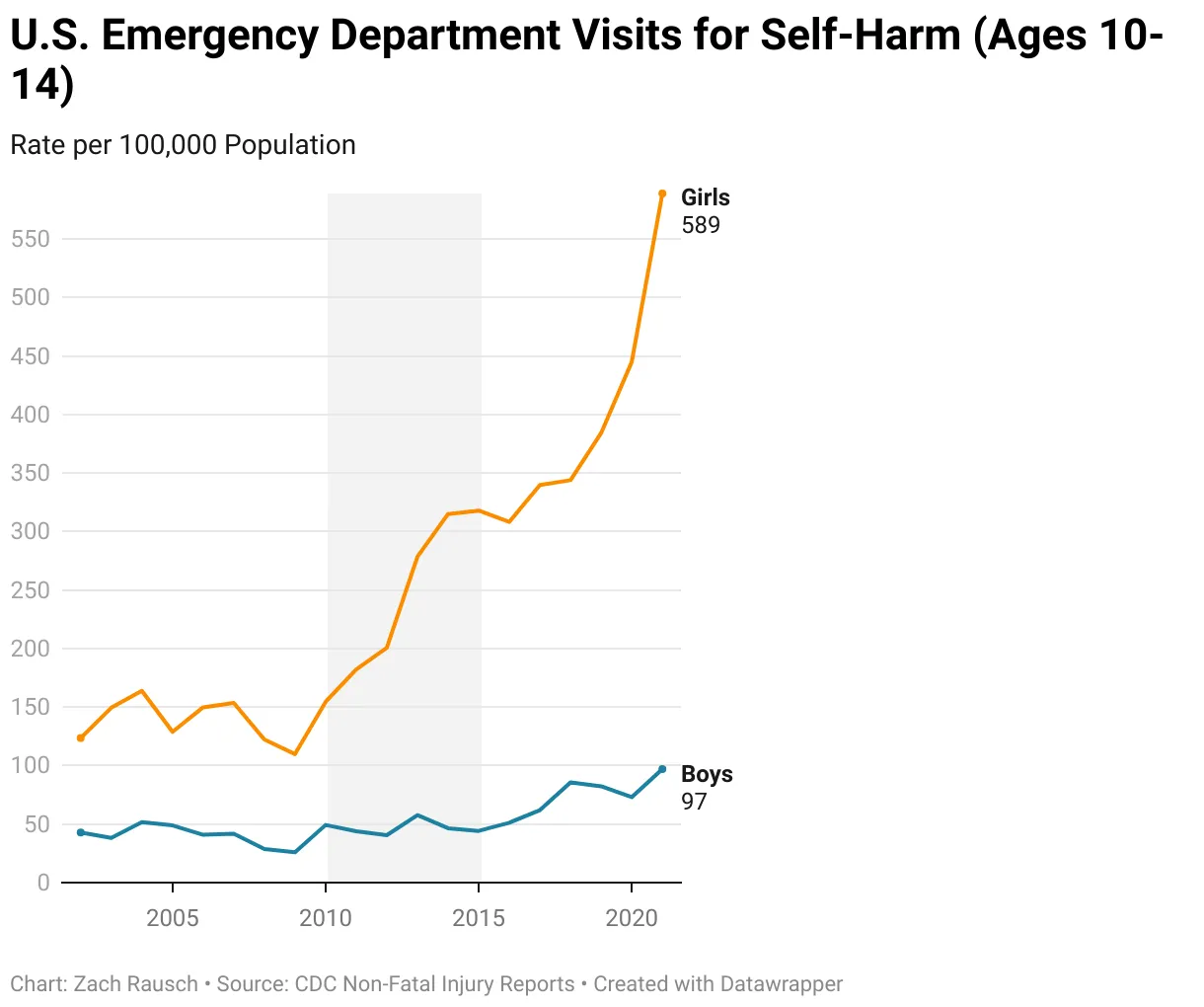

#3: The World changed from 2010-2015

One of Haidt’s main focus is the shift that happened between 2010 and 2015. There may not be a singular moment in time, or defining technology that changed everything and led to the mental health crisis we are facing, but as he points out again and again — this five year period is where the charts start moving up/down sharply.

Thanks to the social psychologist Jean Twenge’s groundbreaking work, we know that what causes generations to differ goes beyond the events children experience (such as wars and depressions) and includes changes in the technologies they used as children (radio, then television, personal computers, the internet, the iPhone).[11] The oldest members of Gen Z began puberty around 2009, when several tech trends converged: the rapid spread of high-speed broadband in the 2000s, the arrival of the iPhone in 2007, and the new age of hyper-viralized social media. The last of these was kicked off in 2009 by the arrival of the “like” and “retweet” (or “share”) buttons, which transformed the social dynamics of the online world. Before 2009, social media was most useful as a way to keep up with your friends, and with fewer instant and reverberating feedback functions it generated much less of the toxicity we see today. [12] A fourth trend began just a few years later, and it hit girls much harder than boys: the increased prevalence of posting images of oneself, after smartphones added front-facing cameras (2010) and Facebook acquired Instagram (2012), boosting its popularity. This greatly expanded the number of adolescents posting carefully curated photos and videos of their lives for their peers and strangers, not just to see, but to judge.

(The Anxious Generation, Introduction)

Take a look at some of the charts shared and notice the gray area highlighting the 2010-2015 five year period. In almost all of the graphs/data you’ll see a jump happen in the gray:

I typically reference the advent of the iPhone as a defining moment, but you can see it took a few years for that technology to lead us into an overuse of phones, social media, and other addictive apps.

We experienced two massive “hinges of history” with the computer and internet. When both were easily accessible in our pockets at any time and any place, well, the world sure changed!

#4. Don’t blame the kids - Social Media Trap

John Spencer is my good friend and co-author of Empower and Launch. He shared a study on his IG (I know, the irony) a few months ago that took me by surprise. You can listen to this Freakonomics episode where they break down the study, but here are the bullet points from their transcript :

Ben Handel is an economist, at the University of California Berkeley. The paper he loved working on was a collaboration with Rafael Jimenez, Christopher Roth, and Leonardo Bursztyn.

They were looking at whether folks felt “trapped” by social media or app/platform use, and what that would look like within a particular group.

They partnered with a company called College Pulse, that has these very large samples of college students. The experiment starts with the basic elicitation, which is how much do we need to pay you to stop using either TikTok Instagram — we did both — for four weeks.

And what we found is that, on average, you would have to pay people $50 to deactivate their TikTok or their Instagram account for four weeks.

That’s where most of the literature stops. Step two is, we wanted to get a sense of something that economists care about called network effects — which is, how does your value of using this product depend on the number of other users?

They found the following: “You need to pay me $50 to not use TikTok for a month. But if I know that a certain amount of my network, friends, whatever, are also not using it for a month, then you only need to pay me, like, whatever, 33 bucks.”

But the most exciting part of the results is the next step. The next step says — we’ve elicited from your network how much they are willing to accept to deactivate their account. Now imagine you’re in control. You’re the boss. And we’re going to ask you, how much are you willing to pay to be social media god and deactivate everybody’s account?

And now what we found is that people are actually willing to pay to deactivate everybody’s account, including their own. And on average for TikTok, for example, they’re willing to pay $30 to deactivate everybody’s account, including their own, for four weeks.

Let’s break that down: Students will actively Pay $30 to deactivate everybody’s (including their own) social media accounts for a month.

We can’t blame the kids. WE put them in this position, where everyone in their network is on social media and has access to phones, and if they don’t have a phone or social media they feel left out.

Haidt does a fantastic job at making sure the kids are not to be blamed in his book. Adults, tech companies, and the government have some serious reconciliation to do about the current environment we have created for our youth.

#5. What tech has replaced matters: Need more opportunities for free play and independence

While the first few chapters lay the groundwork for the problem. You’ll notice most folks talk about the first three recommendations much more than the fourth recommendation from Haidt: More independence, free play, and responsibility in the real world.

When we look at the entire book, the argument is simple. Free play and independence helps adolescents mature and grow. Technology use and overprotective parenting (coddling and scheduled activities included) have taken away much of that play/independence.

Haidt nails this throughout the book, and shares in a recent The Atlantic article:

Before we can evaluate the evidence on any one potential avenue of harm, we need to step back and ask a broader question: What is childhood––including adolescence––and how did it change when smartphones moved to the center of it? If we take a more holistic view of what childhood is and what young children, tweens, and teens need to do to mature into competent adults, the picture becomes much clearer. Smartphone-based life, it turns out, alters or interferes with a great number of developmental processes.

Human childhood is an extended cultural apprenticeship with different tasks at different ages all the way through puberty. Once we see it this way, we can identify factors that promote or impede the right kinds of learning at each age. For children of all ages, one of the most powerful drivers of learning is the strong motivation to play. Play is the work of childhood, and all young mammals have the same job: to wire up their brains by playing vigorously and often, practicing the moves and skills they’ll need as adults. Kittens will play-pounce on anything that looks like a mouse tail. Human children will play games such as tag and sharks and minnows, which let them practice both their predator skills and their escaping-from-predator skills. Adolescents will play sports with greater intensity, and will incorporate playfulness into their social interactions—flirting, teasing, and developing inside jokes that bond friends together. Hundreds of studies on young rats, monkeys, and humans show that young mammals want to play, need to play, and end up socially, cognitively, and emotionally impaired when they are deprived of play.

While it’s easier to point the finger at tech companies, the government, and anyone but ourselves. As a parent, I know that I’m part of the problem. Luckily my kids live in a great neighborhood where they can knock for friends, play in yards and streets and playgrounds. But, I’m often overscheduling them with sports and other activities that definitely take away from this very natural part of maturing and developing.

Haidt shares the recent data that we all have to grapple with: “The numbers are hard to believe. The most recent Gallup data show that American teens spend about five hours a day just on social-media platforms (including watching videos on TikTok and YouTube). Add in all the other phone- and screen-based activities, and the number rises to somewhere between seven and nine hours a day, on average.”

It’s what the phones (and us parents) have replaced independent play with that is alarming, but also fixable. This lesson has been a big one for me as a parent.

Final Thoughts

Our youth are collectively in crisis. Everyone is impacted differently by smartphones, social media, and the lack of a play-based childhood. We can argue about the CAUSE(S) of the crisis, but we cannot argue that this crisis exists.

As a parent and educator, I cannot help but worry about our kids (and all of us).

It’s easy to have an initial knee-jerk reaction when you read this book and see some of the data. However, the conversation about solutions should be as nuanced as possible. We can’t expect phone-free schools to solve all our problems. They obviously have a role in our collective next steps, but as Haidt points out (and some have missed) what the phone-based childhood has replaced is more important than simply removing those devices from our lives.

I hope you join the conversation, look at each situation with an eye for the complexity, and work towards meaningful and relevant learning experiences, both in and out of school. We’ll have to start with empathy, and lead with grace, in order to tackle this as an education community!